Moscow’s new grand strategy is still in gestation. It seeks to maximize connectivity with all, while putting Russia’s own interests first. Managing a large number of very different partners is difficult, but not impossible, as Moscow’s recent experience in the Middle East shows.

Supporters of a free Russia have long dreamed of a day when the Orthodox Church is separate from the state and when elected officials are unafraid to oppose Kremlin ministers. The latter is certainly happening, but among those who are taking advantage of this new freedom first are zealots who speak in a language of aggressive and intimidating conservatism.

Time is on Navalny’s side. If he doesn’t commit a blunder that disenchants potential voters, and if the authorities don’t take the brute force approach of locking him away for a number of years, he could emerge as a key opposition figure between 2018 and 2024.

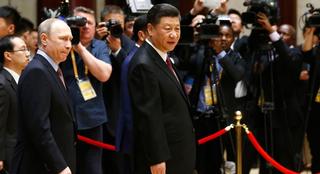

Chinese and Russian leaders won’t always agree, but their deepening cooperation and mistrust of the U.S. is here to stay. Unfortunately, American leaders have shown few signs that they know how to navigate this new reality, let alone manage the competition among great powers as non-Western countries grown in stature.

Washington and Pyongyang will eventually need to resume direct talks. With neither party ready for that yet, at first secret contacts will have to be organized in third countries. In the meantime, de-escalation is the order of the day, and Russia one of its unlikely brokers.

The United States is still the leading power, yet this dominance is no longer uncontested. This contestation is coming in a big way from China and other countries.

Recent US sanctions against China and Russia are signs of the Trump administration’s toughening approach to North Korea. Ironically, these sanctions come on the heels of a UN Security Council resolution imposing new measures against North Korea that the US, China and Russia voted in favor of.

In order to force Pyongyang to abandon its nuclear and missiles programs, the international community has imposed a set of tough economic sanctions. Do they work? And what Moscow thinks about them?

The Russian president’s decision to cull 755 U.S. Embassy employees was not the act of a man ready to give up on relations with the United States.

The cancellation of a controversial ballet at Russia’s premiere theater holds dark clues as to where the country could be headed after Putin.

Mr Putin and Mr Xi have found an unlikely ally in Mr Trump. The latter’s clumsy approach to foreign policy and fractious relations with long-time allies leave the west poorly equipped to push back.

There may be tensions in the Beijing-Moscow partnership, but reverse migration trends among Chinese workers prove that worries about China’s potential conquest of the Russian Far East are unfounded.

It appears that Putin is much less of a disruptor than Trump. He is committed to the status quo at home and would rather join the global establishment than destroy it. In that, he is closer to Clinton than to Trump.

It is not enough for China and Russia to work to reduce US dominance in “the grand Eurasian chessboard.” They have to work on a new continental order that other countries, not just the two of them, would find an improvement over the current situation.

Should Trump be ready to offer Kim Jong-un US security guarantees for his regime in exchange for limiting North Korea’s missile program so that the US West Coast remains safe from North Korean projectiles, Russia could also offer to host a six-party summit in Vladivostok so close to the two Koreas, as well as China and Japan.

In its clumsy attempt to exploit the vulnerabilities of the Sino-Russian axis, the Trump administration misunderstands not only the strength of relations, but also its own desirability as a useful ally.

Twenty-five years after the end of the Soviet Union, Moscow is certainly ready to overcome its old Soviet image. That may have been on the authorities’ minds when they drew up the redevelopment plan. But the only way the authorities could think of redesigning the urban landscape was through Soviet tactics.

At the Belt Road Forum in Beijing, Vladimir Putin once again reaffirmed his personal relations with Xi Jinping without getting into economic specifics. But still, the Russian President managed to get special attention. Russia needs to be satisfied with its political gains from the forum.

Russia has played it cool in the current North Korea crisis, convinced that the spike in tensions will soon subside. Moscow, however, is under no illusion: The security situation on the Korean Peninsula continues to deteriorate and the next alert is just around the corner.

Moscow, with its 13 million residents, is Russia’s most progressive city. But its citizens are not homogenous and cohesive. But after the authorities began intruding on their private space, Muscovites started to unite. They are no longer a resource supporting the political regime. The movement to defend private property rights just might give birth to a sense of civic pride.